No end in diKgosi, BDP brinkmanship

The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) and Chiefs in this country may be heading for an unprecedented showdown with far-reaching political consequences for the ruling party.

A number of chiefs recently met in Mahalapye where they discussed their conditions of work including their relevance in modern Botswana, decrying the continued erosion of their powers. Names of chiefs allegedly joining politics are being thrown about in the aftermath of Kgosi Lotlamoreng II’s electoral victory in the recent Goodhope-Mabule by-election. When contacted for comment, the national coordinator of the Bogosi Association, Kgosi Modise of Sefhare confirmed that indeed his association met in Mahalapye but denied claims that chiefs want to jump onto the political bandwagon. “That certainly is not the view of my association.

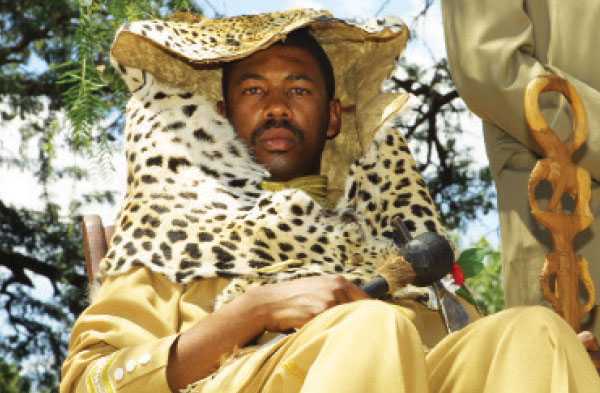

Joining politics is not the solution. Rather, we believe that issues concerning our powers, which we admit have been eroded, can better be addressed through dialogue by all stakeholders,” he said. The uneasy relationship between chiefs and government has existed both during colonial rule and post-independence. However, the decision by Kgosi Lotlamoreng II of Barolong to take leave of absence from his traditional duties in favour of political office when he contested on the opposition Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC) ticket has allegedly rekindled the animosity between the two powers. Before colonial rule, chieftainship was a very potent institution with full judicial and legislative powers.

According to Gloria Somolekae and Mogopodi Lekorwe of the University of Botswana (UB), the chief was both the law-giver and judge. He also regulated the allocation of land, the annual cycle of agricultural tasks, and several other economic activities, including external trade. Between them, the protectorate and post-independence government in this country promulgated a series of laws such as the Order-in-Council, the Native Administration Proclamation Act, the Native Tribunal Proclamation, the Tribal Land Act, the Matimela Act, the Chieftainship Act, the Chieftainship Amendment Act among others. These spelt the end of the powers of the chiefs. For instance, the high commissioner had to recognise somebody for that person to be chief. The high commissioner could censor a chief by way of reprimanding, suspension, expulsion or even banishment. The situation opened up the possibility of puppets to be installed as chiefs. By the same token, the post-colonial regime continued to reduce the powers of the chiefs. The traditional leaders became servants of the colonial government.

After independence, chiefs continued to be reduced to become paid low level civil servants whose status diminished while that of politicians increased. Just like before independence, chiefs in post-independent Botswana also have to be recognised by government. Also, government has the power to remove a chief from office even if the action is not popular with the concerned chief’s subjects. Chiefs lost a lot of privileges including over taxes and stray livestock. Contrary to chiefs’ expectations, when the House of Chiefs was formed after independence, its powers were limited to that of an advisory body in the same way that African Advisory Council was to the protectorate government. Government had made Chiefs to feel that their powers would be restored under the new political dispensation. They had envisaged a House of Chiefs that had legislative powers like the House of Lords in Britain. The founding president of Botswana and leader of the BDP, Seretse Khama, the Paramount Chief of the Bangwato tribe, did not want to alienate chiefs because he was aware that they were and remain very influential among their people.

The opposition Botswana Peoples’ Party (BPP) was led by common men who had no respect for chieftainship, according to Professor Maundeni (Botswana: Politics and Society). “The BPP explicitly stated that chiefs could not be members of the party,” writes Maundeni. Emasculated by the ruling BDP and isolated by the BPP, chiefs got attracted to the Botswana National Front (BNF) which promised, if elected, to establish a house of representatives with legislative powers. Although some chiefs were attracted to the BNF policies regarding chieftainship, the fact that the party was not popular nationally and therefore not likely to win power in the near future, became a disincentive to many of them to join it.

However, Kgosi Bathoen Gasietsewe of Bangwaketse took the risk and joined the BNF, contested the Kanye constituency and beat the then Vice President, Quett Masire. After independence, many African countries had abolished chieftainship arguing that the traditional institution had no relevance in modern society. Says Proctor as quoted by Gloria Somolekae and Mogopodi Lekorwe, “..a chiefly character in a bicameral legislature would seriously impede the modernisation which was seriously needed...and chiefs were too conservative, too interested in preserving their autocratic position and committed to the interests of their tribes rather than those of the nation.”

Cynics argue that the BDP government kept the institution only for political gain due to the influence the traditional leaders had over their subjects. According to Kgosinkwe Moesi, Seretse did everything to avoid war with the chiefs while at the same time infiltrating the institution by appointing to the House of Chiefs people who were sympathetic to the ruling party. Moesi, as quoted by Maundeni says, “...the choice faced by government was whether to meet chiefs head-on or neutralise them quietly. Sir Seretse, a calm, shrewd tactician, ate the young chiefs raw. He appointed BDP loyalists, Mokgacha Mokgadi and Monare Gaborone, de facto ‘paramount’ chiefs who easily dominated the House of Chiefs. Linchwe was sent to Washington DC as ambassador.” Besides having declared lack of interest in the traditional office in favour of the political one, Khama never shied away from telling his tribesmen and women whenever he addressed political rallies that he was their chief.

There is renewed talk that chiefs, just like the workers have been emboldened by the possibility of a change of government following the electoral success achieved by the opposition in the general election last year, are ready to fight for the restoration of their powers by way of joining opposition politics. But social commentator, Ndulamo Morima does not think it realistic for chiefs to envisage a situation where they are completely independent from politicians. “Even in more liberal democracies like South Africa, the President has got the ultimate powers to take action against a chief.

Even the Judicial Service Commission in Botswana can only recommend an individual to be appointed Judge but the final decision resides with the President. He also has the powers to remove a Judge from office,” said Morima. Instead he advocates security of tenure as well as better remuneration for chiefs. “They should, just like the judges, be protected from arbitrary dismissals and any forms of abuse. They should be paid well,” he said adding that, it would be difficult for the opposition, should they assume power, to restore the chiefs the powers they wish for. Efforts to speak to a chief proved futile by press time. While Kgosi Maruje II of North East and Kgosi Galebonwe of Jamataka said they were constrained to discuss the subject, Kgosi Modise of Sefhare did not answer his phone.