Chiefs and politics: time will tell

Nostalgia can be an intoxicant. In worst case scenarios it can be an aphrodisiac, stimulating our desires and activating impulses safely tucked away in the distant past of our memories.

And yet this is the state our nation is gradually falling into, as it navigates its desire – by any means necessary, or so it would seem - for a change of leadership to help it deal with the realities of its body politic. The feeling is palpable. You sense it all over. The air is pregnant with expectation. It’s as if we are sitting on the verge of a major breakthrough. Yet on careful consideration it becomes apparent that it’s all anticipation. Thankfully, such condition breeds innovation. Academics, theorists and men of letters attempt to decode, decipher and break down the mental impulses into a tangible work plan. One on which the spontaneous thoughts and actions, however skewed they may be, could be harnessed into a potent force for change. Hence the current disposition – however fallacious - that diKgosi (traditional chiefs) may hold answers to the political stagnation besieging our beloved nation.

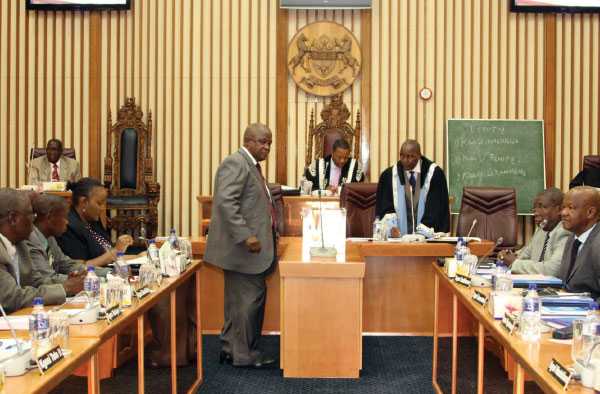

First things first! DiKgosi – the great architects of our nation state – have played their part and continue to do so in various guises, notwithstanding the gradual erosion of their powers. The modern nation state has driven them to the periphery of power. And it was a deliberate maneuver masterminded by politicians in which diKgosi became accessories and ‘silent’ partners. Although unwilling to let go of their powers, the tide of change was such that they either swam or sunk. History teaches us that they sunk at the might of the powerful colonialists and their subsequent proxies, remnants of which currently lord it over diKgosi in the executive arms of government and at the legislatures and judicature. This explains why in that power game diKgosi relented to pressure and acquiesced to political overtures, whose objective was to have Ntlo ya DiKgosi play second fiddle to Parliament and the Executive.

In all fairness, chieftainship has been in crisis since the advent of colonialisation. It could not withstand the winds of change brought about by foreign concepts of neo-liberalism, which made way for the age of reason, in which man’s worth was no longer measured by accumulation of wealth (land and livestock) but by the contents of his brain. This freed the political space to commoners, provided they were educated. Feudalism and bigotry had to make way! As an institution - notwithstanding such pious declarations contained in some of our dictums, such as ‘Kgosi ke kgosi ka batho’ – Bogosi is inherently autocratic. It is a kingdom handed down from generation to generation, although some skeptics have denounced the system as an ‘accident of birth,’ that lends itself to manipulation by pretenders to the throne. They say it has no place in modern societies.

Why then do we still cling to this system whenever we feel that foreign ideologies of governance that we adopted at Independence have failed us? It’s precisely because diKgosi have always been the nerve-centres of human existence, as custodians of people’s traditions, customs and cultures in their journey from primitive war-mongering tribal groupings that thrived on the Law of the Jungle to the contemporary disparate families that wade through the complex maze of the Information Age. The feeling is mutual. Just as the umbilical cord connects the baby to the mother, so does the tribe to the Kgosi. We defer to him. He is the law giver and dispenser of justice and he is Providence in times of hunger. He summons the rains and the people go to farm their lands pleased in the knowledge that their divine protector will not forsake them. And he feeds the hungry, cares for the orphans and the widows. It’s not surprising therefore that all diKgosi that have stood for political office under the current political dispensation have managed to get to Parliament some even attaining the very zenith of power.

It would be a cardinal sin for a tribe to denounce its Kgosi notwithstanding that they do and often abdicate from their thrones! Some do this literally while others abnegate their duties, neglecting their call and leaving their tribes under the tutelage of regents or at worst to its own devices. We have seen this with Kgosi Seretse Khama when he founded the Botswana Democratic Party and the unwavering support he received from his tribe and lately with his son- Ian Khama. The same was true for Kgosi Bathoen Gaseitsiwe when he joined the opposition Botswana National Front and went on to overcome Quett Ketumile Masire despite the enormous resources at the latter’s disposal. It has equally been true for Kgosi Tawana Moremi who joined the BDP and later defected to form the Botswana Movement for Democracy and it certainly hasn’t changed with the recent ascension of Kgosi Lotlamoreng II of Barolong to Parliament under the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC) ticket.

Yet the question remains: to what extent will diKgosi respect inner party democracy? Will they contest primary elections against commoners? Or will their political parties create a special dispensation for them? What really motivates diKgosi to run for political office? Is it to regain the powers usurped by politics and return the nation state to tribal territories or is it for personal profit? It is doubtful whether any political system would want to reverse the strides and gains made in the areas of governance, respect for rule of law, human rights and economic management by returning to chieftainship rule.

In any case, Botswana is not a homogenous society like for example, Swaziland, which has endured Constitutional Monarchy all this time. We are cosmopolitan – that is, multi-cultural and comprising many ethnic groups. If all the diKgosi of these ethnic groups were sent to Parliament it could engender outright tribal conflicts, some of which have remained dormant for time immemorial. Differences over tribal boundaries would immediately rear their ugly head and blow out into the open. Although such tensions already exist, such conflicts have been suppressed by a political system that has centralised power in the executive branch of government away from the local authorities. That’s why Parliament has made it so easy for Land Boards to acquire tribal land from communities without so much of a flinch as to the social or economic implications involved.

Demographics would also come into play- for example, the distribution of one ethnic group over a particular territory, as well as that ethnic group’s claim to the territory (integrity); the extent of its representation in all organs of government- executive, legislature and judiciary – and its control over wealth (natural resources and other factors of production) relative to other tribal groupings. No doubt, these vexing matters would require careful consideration by any political system hoping to maintain social cohesion and harmony among the country’s citizenry. Could the UDC stand the heat? The late Dr Kenneth Koma’s resolution of this matter was to abolish the Ntlo ya Dikgosi under BNF rule and in its stead create a House of Representatives. Would the other constituent members of the UDC – Botswana Movement for Democracy and Botswana Peoples Party – accept this resolution? Only time will tell.